General

Sets of Numbers

Sets

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| Set of all natural numbers | |

| Set of all integers | |

| Set of all rational numbers (Numbers that can be expressed as a fraction) | |

| Set of all real numbers (Any number) | |

| Set of all complex numbers |

Subscript / Superscript

| Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

| Set of all positive integers | |

| Set of all negative real numbers | |

| Set of all integers greater or equal to 12 | |

| Note: 0 is neither positive nor negative |

Summation and Product

Summation

Summation of arithmetic sequence

For arithmetic sequence :

Summation of geometric sequence

For geometric sequence :

Products

Properties (Theorem 5.1.1)

Properties of Integers

:

Closure

Integers are closed under addition and multiplication When you add or multiply an integer, you will get an integer and

Commutativity

and

Associativity

and

Distributivity

Multiplication is distributive over addition (but not the other way around)

Trichotomy

Exactly one of the following is true: or or

Logic

Logic Symbols

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| There exists | |

| For all | |

| p implies q (if p, then q) | |

| p if and only if q This is a connective, like | |

| p if and only if q (p and q are equivalent) (This is the same as ?) | |

| p is equivalent to q (equal, but for logic) This is a “fact”, like | |

| x is an element of A | |

| A is a subset of B | |

| Difference between set A and B | |

| ~p | NOT p (Negation) |

| AND | |

| OR | |

| Set to be a working copy of (not a logic symbol) |

Logic Laws

Commutative

Associative

Distributive

- applying twice: and vice versa

Identities

Universal Bound

Negation

Double Negative

Idempotent

Absorption

Implication

- (Can be deduced from the point above)

- no name for this: this is derived from implication law, distributive law, negation law and identity law

De Morgan’s

These laws can be extended to more than two variables

Logical Arguments

Definition

An argument (argument form) is a sequence of statements (statement forms). All statements in an argument, except for the final one are called premises (or assumptions or hypothesis). The final statement is called the conclusion The symbol, , which is read “therefore”, is normally placed before the conclusion.

Example Argument

Note: this argument is invalid

Valid or Invalid

To say that an argument is valid means that no matter what statements are substituted for the statement variables in its premises, if the resulting premises are all true, then the conclusion is also true. i.e. For an argument to be valid: IF all premises are true, THEN conclusion must be true

Test Validity with Truth Table

- Identify all the premises and conclusion of the argument form

- Construct a truth table showing the truth values of all the premises and the conclusion

- Identify critical rows: Rows in which all the premises are true

- There is a critical row in which the conclusion is false The argument form is valid

- The conclusion in every critical row is true The argument form is valid

Syllogism

An argument form consisting of two premises and a conclusion

Modus Ponens

This is a commonly used form of syllogism: if then

Modus Tollens

Also a commonly used form of syllogism: if then

Rules of Inference

Rules of Inference are Logical Arguments that are valid. Rules of Inference can be chained together to prove more complex logical arguments.

Modus Ponens

if then

Modus Tollens

if then

Generalisation

The conclusion is a more general form of the premise: Anton is a junior (More generally,) Anton is a junior or Anton is a senior

Specialisation

Discard extraneous information to concentrate on the property of interest Ana knows graph algorithms and Ana knows numerical analysis (In particular,) Ana knows graph algorithms

Elimination

When there are two possibilities and one can be ruled out, the other must be the case

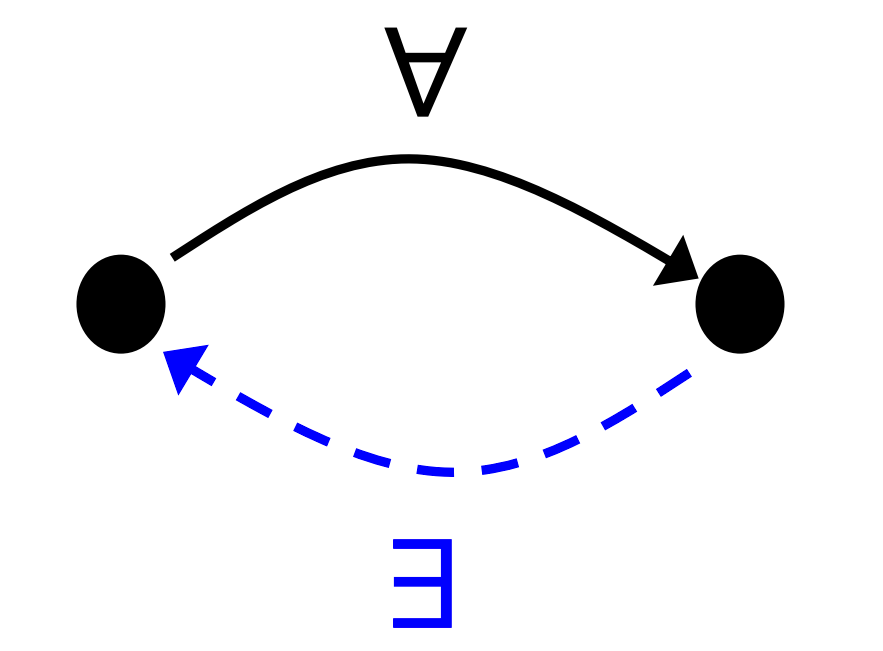

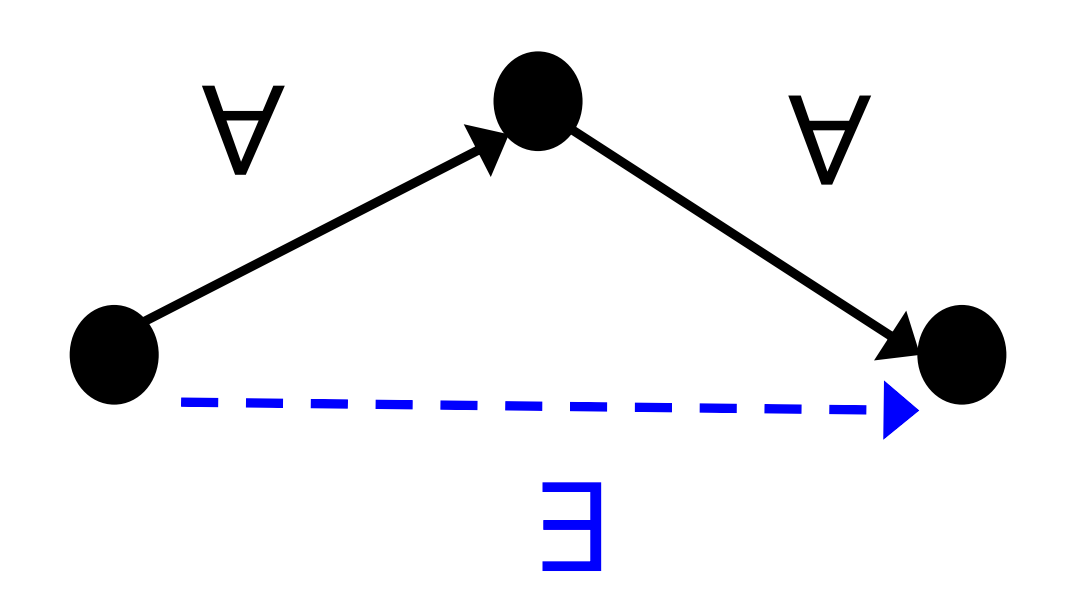

Transitivity

Proof by Division into Cases

Suppose one thing or another is true If in both cases, a certain conclusion follows, this conclusion must also be true

Contradiction

Conjunction Premises

Conditional (if)

Statements of the form is called the hypothesis or antecedent is called the conclusion or consequent “if , then ” ” only if ” ” is a sufficient condition for ” ” is a necessary condition for “

Vacuously True

In the case that is false, is true (vacuously true or true by default)

Implication Law

(Can be deduced from above)

Variants of Conditional Statements

Contrapositive

The contrapositive of is The contrapositive of “if p then q” is “if ~q then ~p” A conditional statement is always logically equivalent to its contrapositive e.g. If Howard can swim across the lake, then Howard can swim to the island If Howard cannot swim to the island, then Howard cannot swim across the lake

Converse

The converse of is The converse of “if p then q” is “if q then p”

Inverse

The inverse of is The inverse of “if p then q” is “if ~p then ~q”

Notes

The converse of a conditional statement the inverse of the logical statement (They are contrapositive) Summary:

- conditional statement contrapositive

- converse inverse

- conditional statement converse

Biconditional (iff)

Statements of the form ” if and only if ” or ” iff ” ” is a necessary and sufficient condition for ”

Logic Connectives

Order of Operations

- ~ (Not)

- and are coequal in order of operation (for CS1231S)

- and are coequal in order of operation

Examples

is unambiguous is ambiguous

Not (Negation)

Symbol

~ (also )

Truth Table

| p | ~p |

|---|---|

| T | F |

| F | T |

And (Conjuction)

Symbol

Truth Table

| p | q | p q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | F |

| F | F | F |

Or (Disjunction)

Symbol

Truth Table

| p | q | p q |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| T | F | T |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | F |

Xor

Symbol

(Not used for CS1231S)

Truth Table

| T | T | T | T | F | F |

| T | F | T | F | T | T |

| F | T | T | F | T | T |

| F | F | F | F | T | F |

Implies

Symbol

Truth Table

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | T |

| F | F | T |

If and Only If

Symbol

Truth Table

| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | F |

| F | F | T |

Logical Equivalence

Definition

Two statements are called logically equivalent iff they have identical truth values for each possible substitution of statements for their statement variables.

Notation

The logical equivalence of statement forms and is denoted by

How to Show Not

There are two ways to show that statement forms and are not logically equivalent:

Truth Table

Find at least one row where their truth values differ

Example

Show that and are not logically equivalent

| T | T | F | F | T | F | F |

| T | F | F | T | F | T | F |

| The last row of the table shows that they are not logically equivalent |

Counter example

Find concrete statements for each of the two forms, one of which is true and the other of which is false

Example

Show that and are not logically equivalent Let be true and be false Will evaluate to true Will evaluate to false Therefore, they cannot be logically equivalent

Quantified Statements

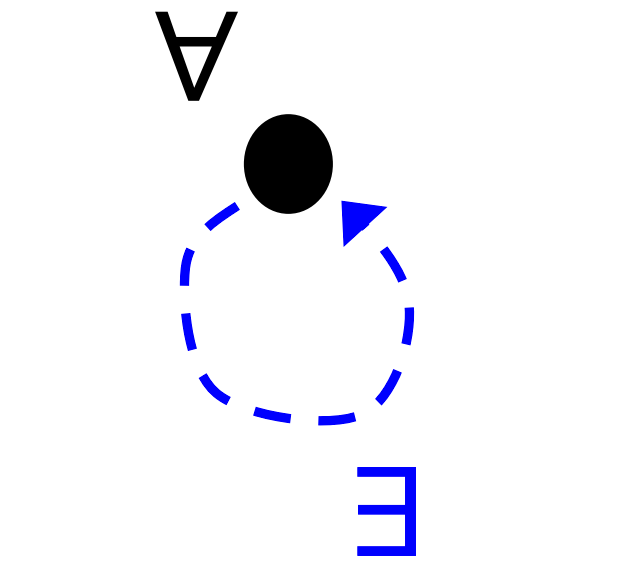

These are known as quantifiers

Universal Statement

Definition

Let be a predicate and the domain of A universal statement is a statement of the form "" i.e. Says that a certain property is true for ALL elements in a set

Example

All positive integers are greater than zero

Keywords

- All

- Every

- Any

Symbol

Negation

Negation of a universal statement (“all are”) existential statement (“some are not” / “there is at least one that is not”)

Notes

A value for for which is false is called a counterexample Implicit Quantification: Sometimes, quantification has to be inferred from context

- If then

- Is interpreted to mean: real numbers , (if then )

Conditional Statement

Definition

Says that IF one thing is true, THEN another thing also has to be true

Example

If 378 is divisible by 18, then 378 is divisible by 6

Keyword

if … then

Symbol

Universal Conditional Statement

Definition

Note: if not specified, “for all” is for the whole domain: , where is the domain of

Equivalent Forms

By changing the domain, a universal conditional statement can be converted to a universal statement: Suppose By narrowing to be the set of all values that make true, set ,

Negation

-(A) -(B) Substitute (B) into (A)

Vacuous Truth

is vacuously true or true by default iff is false for every in (or is an empty set)

Variants

Variants mentioned in Logical Conditional Statements can be extended to universal conditional statements They follow the same relations to each other (statement contrapositive etc.)

Existential Statement

Definition

Let be a predicate and the domain of An existential statement is a statement of the form "" Says that there is at least one thing for which the property is true

Example

There is a prime number that is even

Keywords

- There exists

- There is

- Some

Symbol

Negation

Negation of an existential statement (“some are”) universal statement (“none are” / “all are not”)

Notes

denotes “there exists a unique” or “there is one and only one”

Multiply Quantified Statements

Multiple quantifiers can be used for a single statement e.g.

Negation

Negate statements “from outside in”

Methods of Proof

Direct Proof

Prove that the product of two consecutive odd numbers is always odd

- Let and be the two consecutive odd numbers. 1.1. Without loss of generality, assume that , hence 1.2. Now, for some integer (by definition of odd numbers) 1.3. Similarly, 1.4. Therefore, (by basic algebra) 1.5. let which is an integer (by closure of integers under addition and multiplication) 1.6. Then, , which is odd (by definition of odd numbers)

- Therefore, the product of two consecutive odd numbers is always odd

WLOG

“Without loss of generality” may be abbreviated to WLOG

- This is used before an assumption in a proof which narrows the premise to some special case

- It implies that the proof of this special case can be easily applied to all other cases

Disproof by Counter Example

Prove that the following statement is not true: The product of two irrational numbers is always irrational.

- Let the two irrational numbers be and 1.1. Then, (by basic algebra), which , which is a rational number

- Therefore, the statement “the product of two irrational numbers is always irrational” is not true

Proof by Construction

Prove the following: s.t. (such that) and

- Let

- Note that and

- Also,

Notes

- Proof by construction is where you explicitly find the value with the correct properties

- It is a form of Direct Proof

- No need to explain how you found the result (e.g. 17), you just need to show that the result has the required properties

Proof by Contradiction

- Assume that ~S (not S) is true

- Based on this, use known facts and theorems to arrive at a logical contradiction.

- Since every step of the argument thus far is logically correct, the problem must lie in the assumption (that ~S is true)

- Thus, it can be concluded that ~S is false, that is, S is true

Example

Prove that is irrational

- Suppose not, that is rational 1.1. Then, s.t. (by definition of rational numbers) 1.2. Convert to its lowest term, 1.3. (by basic algebra) (note: this is done by squaring both sides of ) 1.4. Hence, is even (by definition of even numbers, as is an integer by closure) 1.5. Hence, is even (by Proposition 4.6.4 (has been proved somewhere else)) 1.6. Let ; Substituting into 1.3: , or 1.7. Hence, is even (by definition of even numbers) 1.8. Hence, is even (by Proposition 4.6.4) 1.9. So both and are even, but this contradicts that is in its lowers term

- Therefore, the assumption that is rational is false

- Hence is irrational

Proof by Exhaustion

Prove that the difference of two consecutive squares between 30 and 100 is odd

- The squares between 30 and 100 are 36, 49, 64 and 81 1.1. Case 1: which is odd 1.2. Case 2: which is odd 1.3. Case 3: which is odd

- Therefore, the difference of two consecutive squares between 30 and 100 is odd

Note

- Also known as proof by cases, or proof by brute force

- This is suitable when the number of cases is finite

Sets

Properties of Sets

Laws

All sets referred to below are subsets of a universal set

Commutative

Associative

Distributive

Identity

Complement

Double Complement

Idempotent

Universal Bound

De Morgan’s

Absorption

Complements of and

Set Difference

Subset Relations

Inclusion of Intersection

Inclusion in Union

Transitive Property of Subsets

Set Notation

Operations

Cartesian Product

(pronounced cross ) It is the set of all ordered pairs , where is in and is in is the set of all ordered -tuples where times Note: is different from

Union

is the set of all elements that are in at least one of or

Intersection

is the set of all elements that are common to both and

Union or Intersection of Indexed Collection of Sets

Given sets

Difference (Relative Complement)

or is the set of all elements that are in but not

Complement

or is the set of all elements that are in that are not in

Partitions

Sets can be divided into mutually disjoint pieces. Such a division is called a partition, which is also a set e.g. , then is a partition of Elements of a partition are called components of the partition Formally, either: is a partition of a set if the following hold

- is a set of which all elements are non-empty subsets of

- for all

- Every element of is in exactly one element of

- and or: A partition of set is a set of non-empty subsets of such that (note: means there exists a unique)

Power Sets

is the set of all subsets of . It includes Cardinality of power set: , then

Representing Sets

Set Roster Notation

Write all elements between braces Order and duplicates do not matter

Set Builder Notation

the set of all in such that is true: or

Replacement Notation

The set of all where : or

Interval Notation

Notation for subsets of real numbers that are intervals

Comparing Sets

Subset

is a subset of , every element of is also an element of

Proper Subset

is a proper subset of if AND

Others

Cardinality of a Set

denotes the cardinality of a set The number of elements in the set e.g.

Membership

means is an element of means is not an element of

Empty Set

Set containing no elements is NOTE: For all sets ,

Singleton

A set with exactly one element

Disjoint

Disjoint: Mutually Disjoint: for : For

Set of Equivalence Classes

For set and equivalence relation on , the set of all equivalence classes with respect to is denoted (“the quotient of by “) see Equivalence Relations

Set Equality

iff every element of is in and every element of is in Either: Or:

Proving Equality

To prove , prove that: and

Ordered n-tuples

An ordered pair is an expression of the form This is extended to -tuples

Equality

Two ordered pairs are equal iff and This is extended to -tuples

Relations

Relation (between two sets)

Let and be sets, a binary relation from to is a subset of . Given an ordered pair in , is related to by , or is -related to .

Relation on a Set

A relation on set is a relation from to It is a subset of () Note: the arrow diagram of such a relation can be modified so that it becomes a directed graph

Notation

is related to by means means

Domain, Co-domain, Range

Let and be sets and be a relation from to

Domain

is the set

Elements in that are “part of”

Co-domain

is the set

Range

is the set

Elements in A that are “part of”

Inverse Relation

If is a relation from to , then a relation from to can be defined by interchanging the elements of all the ordered pairs of Either Or

N-ary Relations

A -ary relation involves sets. Given sets , an -are relation on is a subset of 2-ary, 3-ary and 4-ary relations are called binary, ternary and quatenary relations respectively

Examples

1: Relation

Let and Suppose we define the relation R such that iff Then, but

2: Defining Relations

Let and Relation is defined from to as: State explicitly which ordered pairs are in and which are in

3: Domain, Co-domain, Range

Let and , and define a relation from to as follows:

Properties of Relations

Properties of Set Relations Note: These are properties of relations, not elements of sets (“element 0 is reflexive” is wrong, “the relation is reflexive”)

Reflexive

Definition

is reflexive iff all elements in the set are related to themselves

Symmetric

Definition

is symmetric iff for all elements that is related to , is also related to

Not Symmetric

Negation of definition of symmetric

Antisymmetric

There does not exist elements where is related to and is related to Let be a relation on set . is antisymmetric iff

Different from not symmetric

- Not symmetric

- At least one pair of elements is only related one way

- Asymmetric

- Not a single pair of elements are related “two-way”, including two of the same element (i.e. no element is related to itself)

- Antisymmetric

- Not a single pair of elements are related “two-way”

Asymmetric

Transitive

Definition

is transitive iff for all elements that is related to , and is related to , is related to

Transitive Closure

The transitive closure of a relation , denoted as , is the smallest superset of that is transitive i.e. To find , add the least number of arrows to the directed graph of to make it transitive Note: when trying to find the transitive closure, keep checking for transitivity after each round of adding arrows Formally, it satisfies all the following:

- is transitive

- If is any other transitive relation that contains (), then

- This means that is the smallest possible relation that is transitive

Example

Set Relation Properties 2024-10-04 02.56.54.excalidraw

⚠ Switch to EXCALIDRAW VIEW in the MORE OPTIONS menu of this document. ⚠ You can decompress Drawing data with the command palette: ‘Decompress current Excalidraw file’. For more info check in plugin settings under ‘Saving’

Excalidraw Data

Text Elements

Embedded Files

cbab65d6da187952222c5b0a286ec6ae3bf5e847:

1e4bb51a12f788d49cec5e422dae640587999f05:

95c5e3e3e5745bb8853e43e00feaabf3653d520d: image_1.png

4dbe37140d70d8134521bd5e2738f6238f412955: image_2.png

Link to original

Relation Induced by a Partition

Given a partition of a set , the relation induced by the partition is defined on as: , a component of such that A partition is the same as an Equivalence Relations, but from different perspectives.

Properties

A relation induced by a partition is reflexive, symmetric and transitive

Example

Let set Let partition of the set Relation induced by the partition is:

Relation Diagrams

Arrow Diagram

Let and . Define relations and from to as follows: ,

Set Relations 2024-10-03 17.49.49.excalidraw

⚠ Switch to EXCALIDRAW VIEW in the MORE OPTIONS menu of this document. ⚠ You can decompress Drawing data with the command palette: ‘Decompress current Excalidraw file’. For more info check in plugin settings under ‘Saving’

Excalidraw Data

Text Elements

1

2

3

1

3

5

S

1

2

3

1

3

5

T

Link to original

Directed Graph

Only for relations on a set. Let , and define on as:

Set Relations 2024-10-03 20.23.45.excalidraw

⚠ Switch to EXCALIDRAW VIEW in the MORE OPTIONS menu of this document. ⚠ You can decompress Drawing data with the command palette: ‘Decompress current Excalidraw file’. For more info check in plugin settings under ‘Saving’

Excalidraw Data

Text Elements

3

4

6

5

Link to original

Relation Composition

Definition

Let , and be sets. Let be a relation, and be a relation. The composition of with () is the relation from to such that: i.e. and are "" related iff there s a “path” from to via some intermediate element in the arrow diagram

Laws

Let , , and be sets. Let , and be relations.

Associative

Inverse

Partial Order Relations

Definition

A relation is a partial order relation (or partial order) iff it is reflexive, antisymmetric and transitive. is used to denote a partial order relation (it replaces in , so ), read ” is curly less than or equal to “

Partially Ordered Set

A set is a partially ordered set or poset with respect to a partial order relation on , denoted by A set with a partial order relation defined on it can be represented and be called a poset

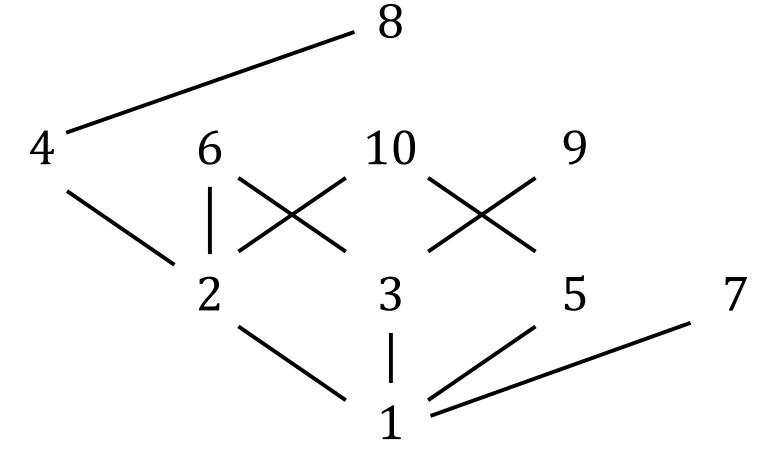

Hasse Diagram

Partial order relations can be represented as hasse diagrams

- Start with a directed graph

- Remove loops on nodes (because reflexive)

- Arrange nodes such that all arrows are pointing up, then remove arrow heads (because antisymmetric)

- Remove arrows that are implied by transitivity

- If there is an arrow from to and to , remove the arrow from to

- Keep repeating to remove as many arrows as possible

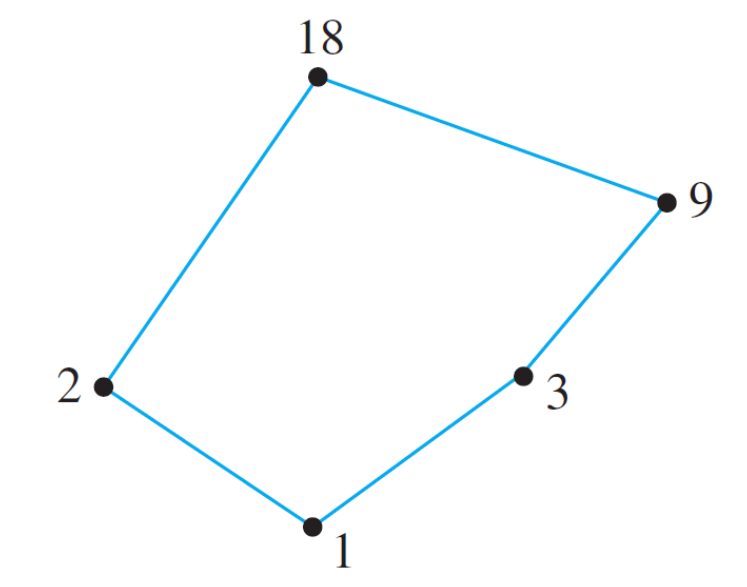

Example

For the “divides” relation on set

Partial Order Relations 2024-10-05 06.21.24.excalidraw

⚠ Switch to EXCALIDRAW VIEW in the MORE OPTIONS menu of this document. ⚠ You can decompress Drawing data with the command palette: ‘Decompress current Excalidraw file’. For more info check in plugin settings under ‘Saving’

Excalidraw Data

Text Elements

Directed Graph

Hasse Diagram

Embedded Files

200bb00677aa83342ccef1087c52e673c454aa82: image.png

acb4d4eb3d78d42155a9149398dea983c5eba8d5: image_0.png

Link to original

Formal Definition

Let be a partial order on a set . A Hasse diagram of satisfies the following condition for all distinct : If and no is such that , then is placed below with a line joining them, else no line joins and

Analogy

Putting on socks and shoes (ignore reflexivity)

- left sock must go on before left shoe, same for right

- but whether the left or right sock goes on first does not matter

- whether the left shoe goes on before the right sock does not matter

- left sock left shoe

- right sock right shoe

- the order is “partial” because there may not be an order between certain elements

- left sock and right sock are not comparable

Common Examples

- The “divides” relation, , on a set of positive integers

- on a set of real numbers

- on a set of sets

Properties of Poset Elements

Suppose is a partial order relation on a set

For example, the hasse diagram of on

Comparability

Elements and of are said to be comparable iff either or . Otherwise, and are noncomparable Hasse diagram: Comparable means having a path between the elements that only goes up In the example and are comparable, but and are not

Compatibility

Elements and of are said to be compatible iff there exists such that and

Hasse diagram: The elements have have a path upwards to the same elements

In the example, and , and are compatible but and are not

Maximal Element

Element of is a maximal element of iff , either or and are noncomparable Hasse diagram: There are no lines upward from the element In the example are the maximal elements

Minimal Element

Element of is a minimal element of iff , either or and are noncomparable Hasse diagram: There are no lines downward from the element In the example is the maximal elements

Largest Element

Element of is the largest element of iff A largest element is always also maximal Note: largest element = greatest element = maximum Hasse diagram: There is a path downwards to all other elements In the example there is no largest element

Smallest Element

Element of is the smallest element of iff A smallest element is always also minimal Note: smallest element = least element = minimum Hasse diagram: There is a path upwards to all other elements In the example is the smallest element

Linearisation

Creating a Total Order Relations from a partial order, without violating the partial order relation Let be a partial order on a set . A linearisation of is a total order on such that

Example

For the “divides” relation on

Linearisations will include:

Linearisations will include:

- etc.

Kahn’s Algorithm

An algorithm that takes a finite set and a partial order on , and outputs a linearisation of Informally:

- Find the a minimal element of

- Remove the element from

- Repeat until

- The linearisation is the elements that were removed, in the order of removal

Total Order Relations

If is a partial order relation on set , and for any two elements and in , either or , then is a total order relation (or total order) on is a total order iff is a partial order and Also called a linear order

Example

The relation on is a total order because

Well-Ordered Set

Let be a total order on a set . is well-ordered iff every non-empty subset of contains a smallest element

Equivalence Relations

A relation is an equivalence relation iff it is reflexive, symmetric and transitive. is commonly used to denote an equivalence relation (it replaces in , so ) This is the same as a partition, but from a different perspective

Equivalence Class

The equivalence class of an element is the component of the partition that contains the element e.g. Partition , the equivalence class of , denoted is Formally, Suppose is a set and is an equivalence relation on . For each , the equivalence class of , denoted , called the class of for short, is the set of all elements such that is -related to . Symbolically,

Lemma Rel.1 Equivalence Classes

Let be a equivalence relation on a set . The following are equivalent for all .

Set of equivalence classes

For set and equivalence relation on , the set of all equivalence classes with respect to is denoted (“the quotient of by “) This is a partition of (Theorem Rel.2)

Theorem Rel.2

Equivalence classes form a partition Let be an equivalence relation on set , then is a partition of

Common Example: Congruence Relations

Congruence

Let and is congruent to modulo iff ( is divisible by ) can be written as

Congruence Relation

Congruence modulo (mod-) relation :

The quotient where is the congruence-mod-n relation on is denoted

Properties

Congruence modulo relation is an Equivalence Relation, i.e. it splits the set of integers into partitions.

Divisibility

Definition

If and are integers and , then is divisible by iff equals times some integer

Notation

means ” divides ”, if and such that

Quotient-remainder Theorem

Given any integer and positive integer , there exist unique integers and such that and , with remainder

Example Use

let: Is a partition of ?

Yes. By the quotient-remainder theorem, every integer can be written in exactly one of the three forms: , , or for some integer . This means that are mutually disjoint and

Functions

Function

A function from a set to a set , denoted is a relation that satisfies the following ( is well-defined)

- (all the in 1. is unique)

or

Let be a relation on sets and i.e. . Then is a function from to iff

or

or

A function from to is a mapping from each element of to exactly one element of

i.e. in the function diagram, there is only one arrow coming out from every element of and every element of has an arrow coming out of it

or

A function is well-defined (exists), if it has the following property:

Definitions

- let be a function. iff

- is the argument of

- is the image of under

- If then is a preimage of

- is the domain of

- is the co-domain of

- range is all possible outputs of , or the setwise image of under

- two functions can be derived from

- is the setwise image of

- is the setwise preimage of

- if , then let

- if , then let

- is the setwise image of , and is the setwise preimage of under

- note: here is not an inverse function although they have the same symbol. can also be written

- e.g. defined . and because and

- Setwise preimage function always exists

- Order of a bijection is the number of times a function has to be composed with itself to result in the identity function

- For a bijection of order :

Equality of Functions

and are equal () iff:

- and , and

Properties of Functions

- An injection (or injective function)

- one-to-one or or equivalently (contrapositive),

- f is not injective iff

- A surjection (or surjective function or “onto”)

- all elements in the co-domain have an input that result in it (range = co-domain)

- A bijection (or bijective function)

- one-to-one correspondence (all elements in co-domain has exactly one item that results in it)

- a function is bijective iff it is both injective and surjective

- If a function has an inverse, then it is bijective

- Inverse

- for , is an inverse of iff

- inverse of is denoted

- inverse functions are unique

- There exists an inverse iff it is bijective (theorem 7.2.3)

Composing Functions

Let and

The composition of f and g, is defined as:

From tutorial 6 Q2,

Identity Functions

The identity function on a set , , is the function from to defined by for all let Theorem 7.3.1:

Inverse Function

Composing a function ith its inverse results in the identity function: Theorem 7.3.2 (let )

Properties

- Composing a function with its inverse results in the identity function (Theorem 7.3.2). Let

- Function composition is associative

- for , and , then

- Function composition is not commutative

- Apart from special cases,

- If and are both injective, then is injective (Theorem 7.3.3)

- If and are both surjective, then is surjective (Theorem 7.3.4)

Functions on

- is the set of equivalence classes on mod- Congruence Relations.

- In terms of functions, it can be taken that the domain is bounded to integer values

- Addition and multiplication functions on are well-defined (the “same” input will result in the “same” output (mod-n))

- Let be the mod-n function, and means mod

- is defined as

- well defined means: for all and all :

- Same for multiplication

- Let be the mod-n function, and means mod

Representing Sequences and Strings

Sequence (infinite)

- A sequence can be represented by a function whose domain is that satisfies for all

- Therefore, any function whose domain is for some represents a sequence

- Sequences can be denoted

- i.e. all the elements of the sequence can be found in

String (finite)

- A string is a finite sequence

- A string or word over set is an expression of the form where and

- is the length of the string. The empty string is the string of length

- Strings can be denoted

- i.e. all the elements of the string can be found in

Equality

- Sequences and

- if their corresponding elements are equal, or for every

- Strings

- if their lengths are equal and their corresponding elements are equal, or for all

Mathematical Induction

Used to prove properties for sequences (e.g. natural numbers)

Closed Form of Sequence

Closed form formula represents a sequence. It shows how the value of sequence term depends on , e.g. for all integers

Sequence Comprehension

Sequences can be represented:

Type signature:

Recurrence Relation

A formula that relates each term to some of its predecessors

e.g. factorial:

0! = 1

n! = n (n-1)! for n 1

Recursive definition of set

For a set ,

- base clause: Specify that certain elements, called founders are in

- recursion clause: Specify certain functions, called constructors, under which set is closed: if is a constructor and , then

- minimiality clause: Membership for can always be demonstrated by finitely many successive applications of the clauses above

Principle of MI (1PI)

Let be a property that is defined for integers and let be a fixed integer. Suppose the following statements are true:

- is true.

- For all integers , if is true then is true.

Then the statement “for all integers ” is true.

Formally

To use

To prove “Fol all integers , a property is true”

Step 1 (basis step): Show that is true

Step 2 (inductive step): Show that for all integers , if is true, then is true, by the following:

Suppose that is true, where is any particular but arbitrarilty chosen integer with (This is called the inductive hypothesis)

Then, show that is true.

Example

Prove that for all integers

- Let

- Basis step: . Therefore, is true.

- Assume is true for . That is,

- Inductive step: (to show P(k+1) is true) 4.1. (because for all integers ) 4.2. Therefore is true

- Therefore, is true for all integers

Principle of Strong MI (2PI)

Let be a property that is defined for integers and let and be fixed integers with . Suppose these statements are true:

- are all true (basis step)

- For any integer , if is true for all integers from through , then is true ( ) (inductive step)

Then the statement “for all integers ” is true

Variation 1

If

- hold

- For every ( implies something further down)

Then holds for all

Variation 2

If

- hold

- For every (, where implies )

Then holds for all

Example

Prove that any whole amount \geq \124 and $5 coins

- Let , for some

- Basis step: Show that hold: (etc. not written here)

- Assume holds for given some

- Inductive step: (To show is true) 4.1. holds (by induction hypothesis), so for some 4.2. 4.3. Hence, is true

- Therefore, is true for

Cardinality

Pigeonhole Principle

Let and be finite sets. If there is an injection , then Contrapositive: Let with . If pigeons are put into pigeonholes, then there must be (at least) one pigeonhole with (at least) two pigeons.

Dual Pigeonhole Principle

Let and be finite sets. If there is an surjection , then Contrapositive: Let with . If pigeons are put into pigeonholes, then there must be (at least) one pigeonhole with no pigeons.

Finite vs Infinite set

A set is said to be finite if it is empty, or there exists a bijection from to the set of positive integers from 1 to

A set is said to be infinite if it is not finite

Cardinality

Finite Set

The cardinality of a finite set , denoted , is

- 0 if or

- if is a bijection

Equality of cardinality of finite sets theorem For finite sets and : iff there is a bijection

Any subset of a finite set is finite (contrapositive: any subset of a infinite set is infinite)

Infinite Sets

Given two sets and , is said to have the same cardinality as , written as , iff there is a bijection

note: we define what is without defining what or is

Another definition: Set is infinite iff there exists a set such that (A proper subset of has the same cardinality as )

Properties of cardinality

The same-cardinality relation is an equivalence relation. For all sets , and

- Reflexive:

- Symmetric:

- Transitive:

Countability

A set is countable iff it is finite our countable infinite. Otherwise, it is uncountable.

Countably Infinite

Theorem 7.4.3: Any subset of any countable set is countable. (Contrapositive: Any set with an uncountable subset is uncountable.)

Lemma 9.4: Let and be countable infinite sets. Then is countable

Definition through bijection with

“aleph zero”

A set having the same cardinality as is called a countably infinite set i.e.

If sets are countably infinite, so is the cartesian product

Definition through sequence

An infinite set is countable iff there is a sequence in which every element f appears (exactly once — whether this is included doesn’t matter) (this is equivalent to the above definition)

Example

is countable

Arrange the elements in a grid as shown:

| (1,1) | (1,2) | (1,3) |

|---|---|---|

| (2,1) | (2,2) | (2,3) |

| (3,1) | (3,2) | (3,3) |

| We can count the ordered pairs following the diagonals: (1,1) → (1,2) → (2,1) → (1,3) → (2,2) → (3,1) etc. (sequence argument) | ||

| The function that represents this is (bijective function argument) | ||

| Therefore, is countable. |

Uncountable Infinite

A set is uncountable if it is impossible to find a bijection from that set to

Theorem 7.4.2: The set of real numbers between 0 and 1, is uncountable

Proposition 9.3: Every infinite set has a countable infinite subset

Cantor’s diagonalization argument

(Prove the above by contradiction)

- Suppose is countable

- Since it is not finite, it is countable infinite

- We list the elementns x_1 = 0.a_{11}a_{12}a_{13}…a_{1n}…x_2 = 0.a_{21}a_{22}a_{23}…a_{2n}…x_3 = 0.a_{31}a_{32}a_{33}…a_{3n}……x_n = 0.a_{n1}a_{n2}a_{n3}…a_{nn}……a_{ij} \in {0,1,…,9}$ is a digit. (For numbers that have two representations 0.499… = 0.500…, we use only the latter representation)

- Now, construct a number (from a diagonal of the above sequence) such that